From the 1960’s until his retirement, Fred Goldberg was a driving force behind a number of the most successful brands in existence. Not only that, but he lived to tell the tale. His recent memoir, The Insanity of Advertising, is brimming with excruciatingly funny anecdotes about his “Mad Man” days, with a wry sensibility and engaging perspective. With his next book about management around the corner, we spoke with Fred about his early experiences, the infancy of Apple, the future of large agencies, the prescience of light-up shoelaces, and many other topics of interest.

DND: Fred, who was an early mentor of yours?

FG: I had so many. Everybody needs someone to support them. At Young & Rubicam, for example, I luckily got to know the president of the agency, Ed Ney. He was quite a distinguished advertising guy. Along with General Foods and Bristol Myers, I was assigned to the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. And it so happens that Ed Ney was close to this account. So I flew down with Ed Ney every now and then to visit the clients in Puerto Rico. We got to know each other and he sort of mentored me, helping me to get promoted to an account supervisor level.

FG: I had so many. Everybody needs someone to support them. At Young & Rubicam, for example, I luckily got to know the president of the agency, Ed Ney. He was quite a distinguished advertising guy. Along with General Foods and Bristol Myers, I was assigned to the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. And it so happens that Ed Ney was close to this account. So I flew down with Ed Ney every now and then to visit the clients in Puerto Rico. We got to know each other and he sort of mentored me, helping me to get promoted to an account supervisor level.

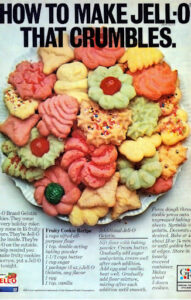

DND: In your book, you share an early-career anecdote about a client (Jell-O) wanting to play it safe and do what they’d always done. Despite you being the expert in the room saying to do otherwise. And then diplomatically, you let the work speak for itself and it won out. What did you take away from this experience?

FG: Well, in the Jell-O situation, I had to go over the Brand Manager’s head and show the work to his boss before it was approved. That’s always a dangerous move. In this case, the ad in question was for a Jell-o cookie recipe and the client’s headline was “Jell-o Cookie Recipe.” They were ready to run it. The ad I got approved was “How To Make Jell-o That Crumbles.” Turns out it was the number one most-read ad out of some 5,000 ads, in both TV Guide and Reader’s Digest, for the entire year.

FG: Well, in the Jell-O situation, I had to go over the Brand Manager’s head and show the work to his boss before it was approved. That’s always a dangerous move. In this case, the ad in question was for a Jell-o cookie recipe and the client’s headline was “Jell-o Cookie Recipe.” They were ready to run it. The ad I got approved was “How To Make Jell-o That Crumbles.” Turns out it was the number one most-read ad out of some 5,000 ads, in both TV Guide and Reader’s Digest, for the entire year.

Standing up for creative work was always a struggle.

DND: As your name and reputation grew, were situations like these greeted with more enthusiasm and less apprehension by clients? Or as you got into bigger rooms, was it always an uphill battle?

FG: Standing up for creative work was always a struggle. When someone sees something new, their tendency is to look over their shoulder and do what has been done in the past. It’s like having a warm diaper on. It’s just more warm and comfortable. You’ve been there before, you know what it feels like and politically there’s a lot less risk.

But as I got more experience over the years, I found my way to many entrepreneurial-minded clients, and people with that kind of mentality. It’s a lot easier to get them to buy into an idea that’s fresh, that’s new, that’s much more likely to be seen, because it’s a bit startling or more relevant. But even still, there’s so much work that I had to defend over the years. Even with some of the entrepreneurial minded people, it could be a challenge.

Take Don Kingsborough, for example, the CEO of Worlds of Wonder. The first commercial we did for Teddy Ruxpin was called ‘Frankenstein.’ Have you seen that?

DND: Yes.

FG: Okay. Don took that home one day, showed it to his wife who happened to have a couple of her girlfriends there that day. They all had kids and they were all, “Oh my God, my kids are going to be scared of that. You can’t show that.” He came back and said he wasn’t going to run the commercial. This was after we shot it. It was a very expensive commercial to produce too. Anyway, it took me five hours but I convinced him to run it. And Teddy Ruxpin generated $110 million in sales in its first year, making it the first American company at the time to achieve this revenue level in its first year, ahead of even Compaq Computer, which reached $105 million.

FG: Okay. Don took that home one day, showed it to his wife who happened to have a couple of her girlfriends there that day. They all had kids and they were all, “Oh my God, my kids are going to be scared of that. You can’t show that.” He came back and said he wasn’t going to run the commercial. This was after we shot it. It was a very expensive commercial to produce too. Anyway, it took me five hours but I convinced him to run it. And Teddy Ruxpin generated $110 million in sales in its first year, making it the first American company at the time to achieve this revenue level in its first year, ahead of even Compaq Computer, which reached $105 million.

At Apple, when we did the 1984 commercial, the only person that never had a doubt was Steve Jobs.

Even some of the most daring entrepreneurial people I worked with, they sometimes hesitated, and you can understand why. I mean, they have a business. Usually, they’re working with investor money. It takes a lot of faith to let the creative speak. Like at Apple, when we did the 1984 commercial, the only person that never had a doubt was Steve Jobs.

DND: Right, I’d like to ask you about that iconic “1984” spot. As it was coming together, did you sense that you were making history?

FG: Not really. The 1984 commercial was a part of some forty pieces of advertising that were presented for the introduction of the Macintosh. All of the work was very good. As far as making history, we thought the product itself was really the breakthrough. And the commercial, after it was produced, was actually roadblocked by John Sculley and members of the board of directors. Those guys got their assholes tight, and they thought Apple was going to look like they were crazy running a thing like that. Well, look what happened. The world would be a lot different today if that commercial hadn’t run.

FG: Not really. The 1984 commercial was a part of some forty pieces of advertising that were presented for the introduction of the Macintosh. All of the work was very good. As far as making history, we thought the product itself was really the breakthrough. And the commercial, after it was produced, was actually roadblocked by John Sculley and members of the board of directors. Those guys got their assholes tight, and they thought Apple was going to look like they were crazy running a thing like that. Well, look what happened. The world would be a lot different today if that commercial hadn’t run.

DND: What was the atmosphere like during that shoot?

FG: In all my years, I’d never been on a production like that. It was like shooting a short film over three days. Of course Ridley Scott, the director, was already famous because he had done Blade Runner and Alien. He was like a painter, the way he worked. Putting the set together. He was the guy that came up with the idea for those jet engines that you see hanging on the wall, and all sorts of other details that added greatly to the scenes and the story. Little things that you wouldn’t notice unless you studied every frame and hardly anybody noticed but it was there. It added to the pastiche of the whole thing. It was a great, incredible commercial.

One of the smartest things that I ever did: I never turned down a phone call from someone who called me.

DND: Apple, Dell, Kia, and so many other brands you helped to propel are still going strong. Yet they came to you in their relative infancy. Besides an entrepreneurial spirit, what did you see in these brands at the time? Was there a common thread?

FG: It wasn’t always me who had the foresight; it was the agency and our people and not necessarily me who helped achieve many successes. But I will say that I received a lot of criticism for doing this, although in hindsight, it was one of the smartest things that I ever did: I never turned down a phone call from someone who called me. I mean, I had some crazy people call and I wasted some time. I had a lot of small accounts but amongst those small accounts, I ended up with some giant ones. But I never turned down a conversation, because there might be an opportunistic idea in there. The direct answer is that with entrepreneurial folks, we were allowed and even encouraged to do more inventive creative work. At least at the beginning of a relationship.

DND: And how did you envision what would work well in the market?

In my upcoming book, I talk about a famous showman, a guy named David Belasco. He said, “The art of showmanship is giving people what they want just before they know they want it.” I’ve referred to his observation a number of times because it’s often just a matter of timing. You also have to have a bit of luck. And sometimes, a client would bring me something that was just too early. The world wasn’t ready for it yet.

DND: Can you give an example?

FG: I was just talking with a guy who was a client of mine, Jonathan Rosenthal. He introduced a concept called NetAir. This is back in the 80s. We did some terrific promotion and advertising, but the economics of the business back then were not in its favor. Now, there’s on-demand private aircraft. It was just ahead of its time.

I had another guy come in, Jim Lavelle. He opens his briefcase up and puts blinking lighted shoelaces, which were activated by movement, on my desk. I thought it was a terrific idea. But again, it was something that was too early and didn’t catch. Then a few years later, L.A. Gear and other sneaker manufacturers started putting blinking lights in the heels, and that’s what took off. There were so many of these types of situations.

Everything was about the work, no matter what we did.

DND: In The Insanity of Advertising, you talk about how over time, large ad agencies become commodities and grow indistinguishable from one another. With so many creative talents joining forces under one roof in an agency setting, why does this happen? How did you push against it when you had your own agency?

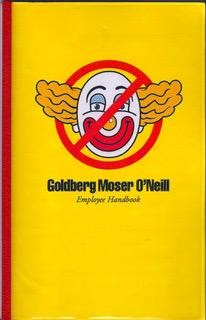

FG: I personally worked really hard at branding our agency. I have a chapter in my new book called “Why Would Anyone Want a Clown as Part of Its Branding?” It talks about everything that we did to ensure that people understood what our objective was, what our goal was, what we would and would not tolerate. Tom Peters and Nancy Austin from Stanford wrote a book called Passion For Excellence which is about being passionately committed to your goals and your work. I bought hundreds and hundreds of those books. Everyone that joined the agency got a copy of that book. We really tried to instill and practice that passion.

FG: I personally worked really hard at branding our agency. I have a chapter in my new book called “Why Would Anyone Want a Clown as Part of Its Branding?” It talks about everything that we did to ensure that people understood what our objective was, what our goal was, what we would and would not tolerate. Tom Peters and Nancy Austin from Stanford wrote a book called Passion For Excellence which is about being passionately committed to your goals and your work. I bought hundreds and hundreds of those books. Everyone that joined the agency got a copy of that book. We really tried to instill and practice that passion.

Everything was about the work, no matter what we did, we tried to make sure everybody did something creative with it. Whether it was a media plan or a promotion or… I mean, this is way beyond the ads. It was everything from our flower arrangements to holiday cards to the presentation of our creative work. Most other ad agencies had offices and doors and hierarchies and protocols and all this stuff, and we didn’t. We focused on our product and being viewed as a creative enterprise.

DND: So how did you breed the right culture for success?

FG: I really think we had smarter people than most agencies did. We hired based on intelligence, merit, and a demonstrated commitment to creative ideas and understanding the importance of that. I’m about to publish our employee manual in addition to my new book, just to make it available. You can soon get the world’s best employee manual for a buck. Nick Wale at DSP, a very successful publisher, has agreed to do it.

FG: I really think we had smarter people than most agencies did. We hired based on intelligence, merit, and a demonstrated commitment to creative ideas and understanding the importance of that. I’m about to publish our employee manual in addition to my new book, just to make it available. You can soon get the world’s best employee manual for a buck. Nick Wale at DSP, a very successful publisher, has agreed to do it.

Prior category experience is an irrelevant consideration, but you do have to learn each new category in depth as you go.

DND: You’ve had influence over the growth of so many categories, including consumer electronics, automotive, and packaged goods. How were you able to leverage your expertise and skills from one seemingly unrelated category to another?

FG: Here’s one of the most persuasive things that we did in new business. I always said this in every presentation, when we had a prospect in a category that we had never worked with: “Before we had Apple, we didn’t have a computer. Before we had Kia, we didn’t have a car. And before we had 3M, we didn’t have a diskette.” Prior category experience is an irrelevant consideration, but you do have to learn each new category in depth as you go.

I had another thing I did. I had a sheet of paper with every client that was current and some of the past, like Steve Jobs. And I listed them as references; I gave their direct contact numbers on this reference sheet and I said, “Please call every one of these clients.”

Just having that piece of paper got us a lot of credibility and business, and I wasn’t afraid if they were to call because all those people I knew were going to give the agency a positive recommendation. Whenever we got a new business, and the listed people were called as references, I gave them a bottle of Cristal Champagne. Which I’m sure they didn’t forget. Plus, we had given them great work.

DND: What happens when you’re onto something great and a client loses their trust?

FG: Then they wind up “confidgeting,” That’s where you keep screwing around with something that’s already perfect. Pretty much perfect. In my upcoming book, I have the whole history of how we parted with Dell and what happened after it. It’s absolutely amazing. I mean, they went through 8 or so agencies after us. In search of the end of the rainbow. Never to be found.

The first one was J. Walter Thompson, which lasted nine months. They did some of the stupidest and most inane advertising ever. Then they went to Doyle Dane Bernbach, BBDO, Young & Rubicam, then Ogilvy, and then WPP created an agency dedicated to Dell called Enfatico. 1,000 people were going to work there. They worked for a year. They never did an ad I’m told; they never were able to produce an ad in that year. It all got folded away a year later into the Y&R agency. If there’s another word for insanity, I would have used it.

What’s worse is that Michael Dell was there for the whole thing. I’m sure he has memories of some of this stuff. I’ve communicated with him a couple of times over the past 25 years. I don’t know how he let this all happen. I guess it’s a case of bigger is not better.

DND: I know you ultimately had to walk away from Dell. But you also, in the book, talk about the artistry of getting fired. Because high profile agencies don’t often get gently let go back into the world. They’re vocally and publicly fired. Is this a necessary evil in the advertising profession?

FG: There’s an old expression that says the day you get the account is the day you started losing it and it’s probably true. It’s worse today I’m sure. From what I see, far worse. Something inevitably happens. It’s usually a marketing guy that changes and he’s told, usually by the CEO, “You run the marketing and the advertising.” It’s a tough business in that regard. It’s very difficult to protect yourself. Clients steal people from you. They have unspoken friends at other agencies. They cut different deals behind your back and you don’t know about it. It’s very hard. But we picked up another computer company, Micron, only a few days after we officially resigned from Dell. Now that’s how you resign an account artistically. Sweet!

FG: There’s an old expression that says the day you get the account is the day you started losing it and it’s probably true. It’s worse today I’m sure. From what I see, far worse. Something inevitably happens. It’s usually a marketing guy that changes and he’s told, usually by the CEO, “You run the marketing and the advertising.” It’s a tough business in that regard. It’s very difficult to protect yourself. Clients steal people from you. They have unspoken friends at other agencies. They cut different deals behind your back and you don’t know about it. It’s very hard. But we picked up another computer company, Micron, only a few days after we officially resigned from Dell. Now that’s how you resign an account artistically. Sweet!

Most of what’s running now on digital media is far from creative.

DND: With all the emphasis on measurability these days, how important are quantifiable metrics versus creative impulses and doing what’s unexpected and feels right?

FG: I don’t think they have to necessarily be divided. But the problem with today, with everything happening with digital media, is you don’t know what you’re really getting. With Dell, you ran a newspaper ad and knew the next day how many computers were sold off that ad. It’s mostly not an issue of “creative impulses” anymore, because most of what’s running now on digital media is far from creative. Nevertheless, on some level, factors like awareness, image, and unit sales all matter. Advertising still needs to work and be measured.

But today, people have no idea about Facebook and Google’s actual effectiveness. Except those tracking unit sales. But those clocking ‘clicks’ and such….forgetaboutit. I laugh at these numbers that people have… They buy the media, they spend five million dollars on Facebook and have no clue what they’re actually getting. Now look at what’s coming out the last couple of weeks, I don’t know if you’ve read, Facebook… People don’t even know what they’re getting when they get these numbers about their audiences. It could be the same people 55 times or it could be totally the wrong people. It’s very crazy. This is all under the guise of supposedly “quantifiable metrics.”

DND: When can we expect your next book?

FG: Well, I finished writing and I’m waiting on my publisher. So I would think two, three months. It’s called Indubitable Eyewitness Observations (Management Matters).

DND: What’s an example of an ad that impressed you since you retired?

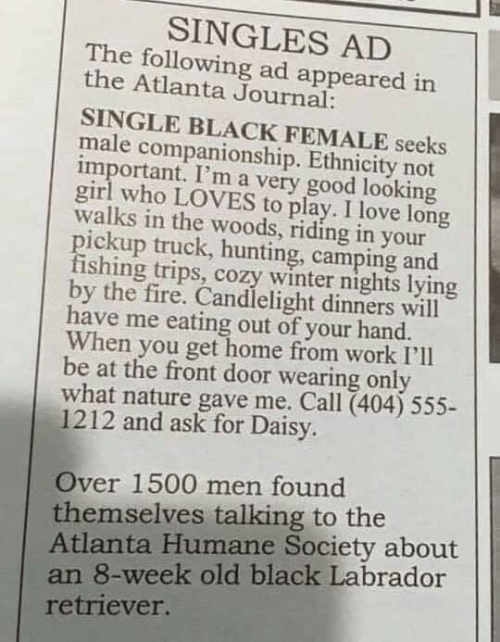

FG: This small space ad, it ran in the Atlanta Journal. You read this thing and it’s a full paragraph about two inches of small type, a Classified singles ad. It’s so perfectly written. They got hundreds and hundreds of men that called the number thinking it was for a single lady. It’s from a Humane Society in Atlanta. Turns out it’s to adopt a dog. So if anybody questions whether advertising works, there it is. It cut through the clutter, it grabbed the reader’s interest, and it was read in its entirety. And it offered something they didn’t expect. I would be very surprised if that pooch didn’t find a home as a result.